On the 26th and 27th May I carried out two workshops designed to compare improvisation and performative engagement between the two intermedial stages of PopUpPlay and iMorphia. The performers had previously participated in the last two workshops so were familiar with iMorphia, but had not worked with PopUpPlay before.

My sense that PopUpPlay would provoke improvisation as outlined in the previous post, proved correct, and that iMorphia in its current form is a constrained environment with little scope for improvisation.

The last workshop tested out whether having two performers transformed at the same time might encourage improvisation. We found this was not the case and that a third element or some sort of improvisational structure was required. The latest version of iMorphia features a backdrop and a virtual ball embodied with physics which interacts with the feet and hands of the two projected characters. This resulted in some game playing between the performers, but facilitated a limited and constrained form of improvisation centred around a game. The difference between game and play and the implications for the future development of iMorphia are outlined at the end of this post.

In contrast, PopUpPlay, though requiring myself as operator of the system, resulted in a great deal of improvisation and play as exemplified in the video below.

OBSERVATIONS

1. Mirroring

The first workshop highlighted the confusion between left and right arms and feet when a performer attempted to either kick a virtual ball or reach out to a virtual object. This confusion had been noted in previous studies and is due to the unfamiliar third person perspective relayed to the video glasses from the video camera located in the position of an audience member.

Generally the only time we see ourselves is in a mirror and as a result have become trained to accepting seeing ourselves horizontally reversed in the mirror. In the second workshop I positioned a mirror in front of the camera at 45 degrees so as to produce a mirror image of the stage in the video glasses.

I tested the effect using the iMorphia system and was surprised how comfortable and familiar the mirrored video feedback felt and had no problems working out left from right and interacting with the virtual objects on the intermedial stage. This effectiveness of the mirrored feedback was also confirmed by the two participants in the second workshop.

2. Gaming and playing

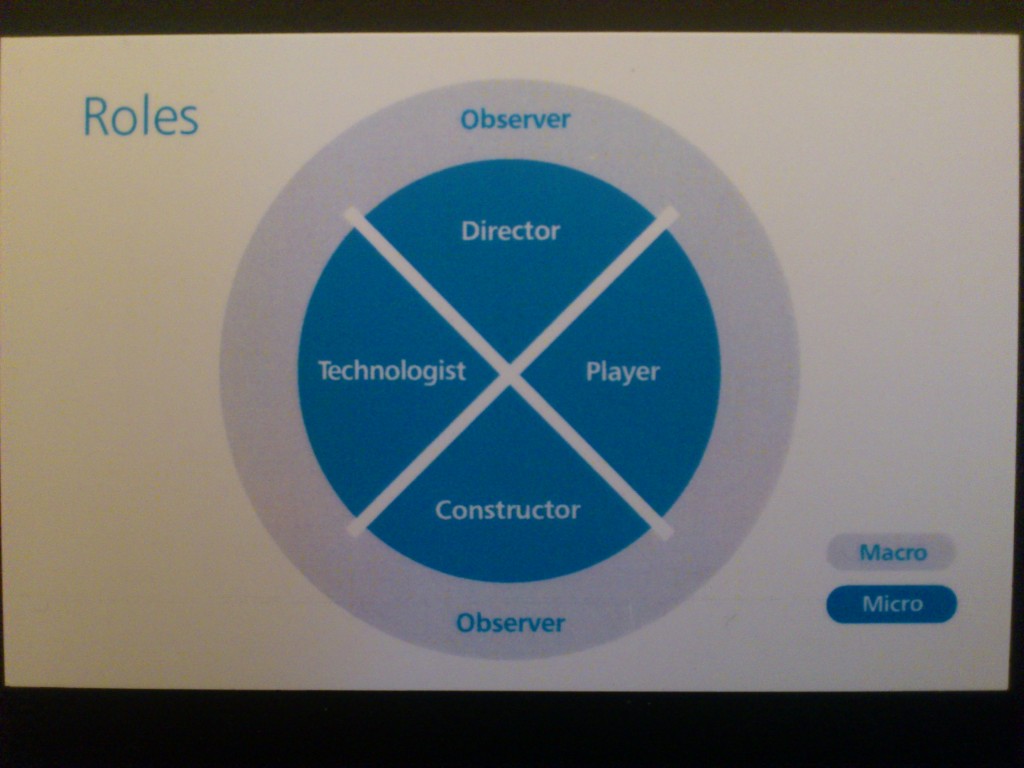

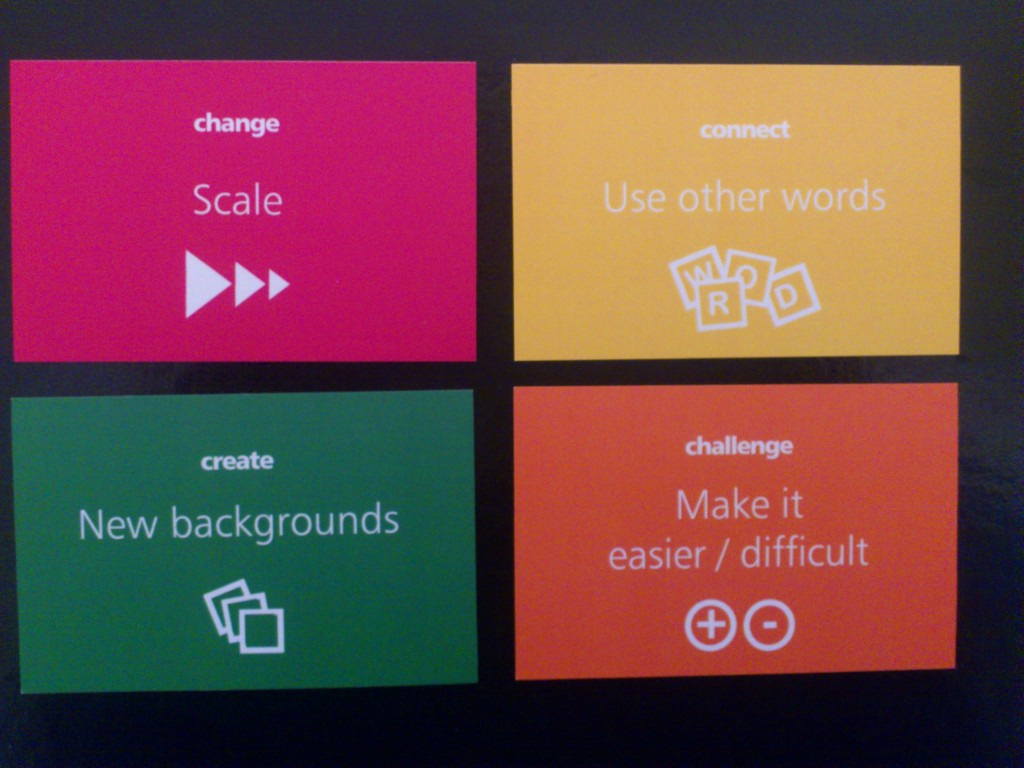

The video highlights how PopUpPlay successfully facilitated improvisation and play, whilst iMorphia, despite the adding of responsive seagulls to the ball playing beach scene, resulted in a constrained game-like environment, where performers simply played a ball passing game with each other. Another factor to be recognised is the role of the operator in PopUpPlay, where I acted as a ‘Wizard of Oz’ behind the scenes director, controlling and influencing the improvisation through the choice of the virtual objects and their on-screen manipulation. My ideal would be to make such events automatic and embody these interaction within iMorphia.

We discussed the differences between iMorphia and PopUpPlay and also the role of the audience, how might improvisation on the intermedial stage work from the perspective of an audience? How might iMorphia or PopUp Play be extended so as to engage both performer and audience?

All the performers felt that there were times when they wanted to be able to move into the virtual scenery, to walk down the path of the projected forest and to be able to navigate the space more fully. We felt that the performer should become more like a shamanistic guide, able to break through the invisible walls of the virtual space, to open doors, to choose where they go, to perform the role of an improvisational storyteller, and to act as a guide for the watching audience.

The vision was that of a free open interactive space, the type of spaces present in modern gaming worlds, where players are free to explore where they go in large open environments. Rather than a gaming trope, the worlds would be designed to encourage performative play rather than follow typical gaming motifs of winning, battling, scoring and so on. The computer game “Myst” (1993) was mentioned as an example of the type of game that embodied a more gentle, narrative, evocative and exploratory form of gaming.

3. Depth and Interaction

The above ideas though rich with creative possibilities highlight some of the technical and interactive challenges when combining real bodies on a three dimensional stage with a virtual two dimensional projection. PopUpPlay utilises two dimensional backdrops and the movements of the virtual objects are constrained to two dimensions – although the illusion of distance can be evoked by changing the size of the objects. IMorphia on the other hand is a simulated three dimensional space. The interactive ball highlighted interaction and feedback issues associated with the z or depth dimension. For a participant to kick the ball their foot had to be colocated near to the ball in all three dimensions. As the ball rested on the ground the y dimension was not problematic, the x dimension, left and right, was easy to find, however depth within the virtual z dimension proved very difficult to ascertain, with performers having to physically move forwards and backwards in order to try and move the virtual body in line with the ball. The video glasses do not provide any depth cues of the performer in real or virtual space, and if performers are to be able to move three dimensionally in both the real and the virtual spaces in such a way that colocation and thereby real/virtual body/object interactions can occur, then a method for delivering both virtual and real world depth information will be required.